A veteran may return bodily from war, but his mind often remains in the war-zone. Walking down to the shops, his wife will try to engage him in chat about everyday issues – but he is scanning the windows and roofs of buildings for snipers. A car backfires and she scarcely breaks step – but he has crashed over a front garden wall and is lying prone trying to discern the direction of ‘the shot’.

In a pub the veteran will insist on sitting with his back to the wall, in a position that allows him to scan the entrance and exit doors. Family and friends think that a stranger has returned to them, but the veteran will think that it is them who are out of step and not him. To them his behaviour is bizarre and irrational, for the veteran, however, it is not only rational, but also necessary – to protect his family and himself.

For those veterans who are additionally suffering from conditions like combat-related PTSD, things can get even more out of control. While the authorities prefer to ignore and hide the number of veterans who are suffering from these types of conditions, an additional problem to identifying veterans with PTSD is that they themselves are often very resistant to any suggestion that they may be suffering from ‘mental problems’ (Surely, hard, tough soldiers would not succumb to a condition like PTSD, they think).

Veterans can also be very suspicious of any interest from outsiders in them and are often averse to answering question. Jimmy Johnson, a Northern Ireland and Aden veteran serving a life sentence in HMP Frankland, has campaigned on behalf of his fellow veterans for over three decades. He has written extensively about this issue and the following guide to ‘Recognising Combat-related PTSD’ was adapted from Jimmy’s writings.

Recognising Combat-related PTSD

Veterans will not tell their wives, families or friends that they are suffering from Combat PTSD

– because they simply do not know themselves.

A veteran suffering from the hidden wound of PTSD appears to live in a separate world – but the condition will often show itself in several ways:

- Strange Behaviour at Home – The veteran’s behaviour at home begins to get on his wife and family’s nerves. He often sits at home and hardly ever speaks to his wife and family. The veteran does not seem to care or worry about the running of the family home, he doesn’t seem interested.

- Work – The veteran after a few weeks back home manages to get a job – then, often after only a few days or weeks, he packs the job in.

- Horrors –The veteran suffering from combat-related PTSD brings home ‘new’ sleeping habits: nightmares. He may also experience ‘flashbacks’ to traumatic incidents experienced during combat.

- Drink and Drugs – The veteran suffering combat-related PTSD starts drinking alcohol or taking drugs. This can be an attempt at self-medication – to take away the memory and pain.

- Got to be Alone – The veteran may have a good job and working as normal then suddenly he disappears, away from everyone.

- Wrong Information – The veteran suffering from combat-related PTSD will at times feel very nervous for no apparent reason.

- Sounds / Noises – Sudden loud noises like fireworks can dredge-up suppressed memories of combat, but veterans can also feel threatened if they hear any sounds they cannot recognise (especially at home).

- Panic – A veteran will not stay inside a small room when other strangers are present – he will leave.

- Mood Swings / Depression – The veteran has very bad mood swings and suffers from bouts of depression and thoughts of suicide.

- The veteran has terrible outbursts of rage and resorts to violence easily – The veteran explodes with rage at small trivial things. Sometimes the rage explodes into fury and violence is used.

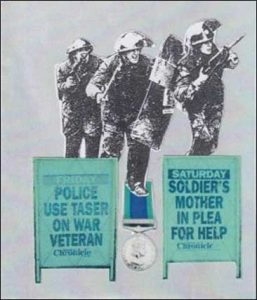

The veteran may well end up in prison.

And this happens on a much larger scale than is generally known.

For many veterans the aftermath of conflict often leads to

Alcoholism, Divorce, Homelessness, Prison or Suicide.

Redemption isn’t coming soon

I’m stuck here with these hidden wounds

All the things they made me do

They haunt me

Lines from the dEUS song Hidden Wounds about Jimmy Johnson.

Any veteran, or family members, who want to understand how and why military training, service life and tours-of-duty might have affected them should watch ‘You are not in the Forces Now’ by psychologist and Australian Vietnam-War veteran Nic Fothergill. This video, of a one hour lecture he gave to Aussie Vietnam veterans and their families, is a good starting point:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZK2CeULAJuE

Article by Aly Renwick, who co-founded Veterans In Prison with Jimmy Johnson. Aly served for 8 years in the British Army (1960-8).