THE ACCRINGTON PALS:

The Rise & Fall of the Pals Battalions in World War One

by Aly Renwick.

During the early part of Queen Victoria’s reign, there had always been a fair amount of admiration in Britain for the German people and their culture and literature. After all the British Royal family were of German lineage themselves. But these cordial feelings began to change in the late Victorian period, especially after the Prussian victory in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71.

After starting to view Germany as an increasingly powerful rival both for business and territory, negative comments about that country then began to appear in Britain. By the early 20th century anti-German feeling was being stirred-up in papers like the Daily Mail. Who in one story bid their readers to refuse service from Austrian or German waiters at restaurants – because: ‘They might be spies’.

After World War One started Britain quickly produced a tidal wave of propaganda depicting the Germans as ‘Huns’ – capable of despicable acts of infinite cruelty and violence. And an anti-German mood, fuelled by Government propaganda and the patriotic Music Halls, swept across Britain. This led to some riots, with assaults on those suspected to be German and the looting of shops and stores owned by people with German-sounding names.

Even pets were not exempt, with the English Kennel Club having to rename the German Shepherd breed of dog, as the ‘Alsatian’. So strong was this anti-German feeling that the British royals were quietly advised to change their names. So, in 1917, King George V issued a proclamation declaring that he and all the other descendants of Queen Victoria were changing their German surnames – be they Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Battenberg, Saxony, or Hesse – to Windsor.

The Pals Battalions

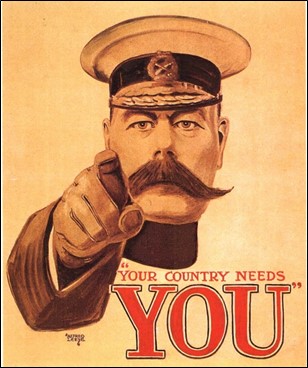

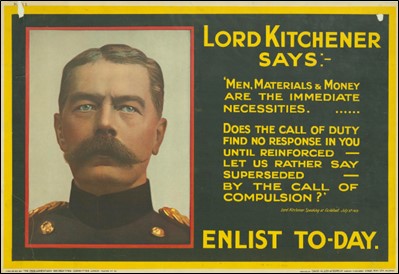

On 4th August 1914, when Britain declared war on Germany, the size of the British Army was 247,432 regular troops. When Field Marshal Lord Kitchener was appointed Secretary of State for War, he was given the task of recruiting the numbers that would be needed to fight an industrialised war against another European imperialist nation. With the war already begun, Kitchener needed a way to recruit hundreds of thousands of soldiers quickly.

Recruited from specific close communities at home, or work, the Pals Battalions were formed by exploiting the patriotic fervour that the war had aroused. Under Kitchener’s tutelage, but organised locally by prominent people like MPs, mayors, gentry and factory owners, the Pals were composed of volunteers eager ‘to teach the Hun a lesson’. Their strength was based on a community spirit, because they were all friends, neighbours, relatives and workmates.

In the midst of the country-wide anti-German propaganda campaign, eager young ‘King and Country’ patriots flocked to enlist. In just five days in Liverpool, Lord Derby recruited enough volunteers to set up 3 Pals Battalions; Manchester, in two weeks, raised 4; Glasgow saw over 1,000 Pals volunteering in a single night – from the Corporation Tramways Department. Within two months 50 Pals Battalions had been formed, or were in the process of forming.

The mayor of Accrington, Captain John Harwood, offered to raise a Pals battalion and recruitment quickly began. The Accrington Pals were recruited mainly from that town with a few from its neighbours – Burnley, Chorley and Blackburn. By the end of the month over 1,000 men had responded to form a battalion with a distinctive local identity.

The Battle of the Somme

In February 1916, now incorporated into the 31st Division, the Accrington Pals were ordered to the front-line in France near the Somme River. They were to take part in what the Generals called the ‘brilliant advance of July the First’. Their objective was to take the hilltop fortress of Serre, guarded by Germans of the 169th (8th Baden) Infantry Regiment.

For a week before the ‘big push’ British artillery pounded the German lines, but the enemy were well dug-in and only partially affected by the shelling. The men of the Accrington Pals, however, were told that the Germans would all be wiped out – and therefore be incapable of defending their lines. And the Pals were told to just walk across and take their trenches.

On July 1st, 1916, at 7.20am, whistles sounded and the orders to advance were shouted. And the Accrington Pals went ‘over the top’ and moved forward into ‘no man’s land’ to face their fate. The Germans, however, were already scrambling from their deep underground shelters clutching their machine guns and rifles, which they quickly brought to bear on their advancing enemy.

An observer later stated that the Pals were cut down like: ‘Swathes of cut corn at harvest time’. It was recorded that out of the 720 Accrington Pals who took part in the attack, 584 were killed, wounded or missing, at the end of the day. Back home in Accrington, there were initial reports of: ‘Success on the Somme’, before the true situation started to leak out.

It gradually became clear that whole neighbourhoods had lost most of their young men. Because in every street, many of the curtains were not opened (signifying a loss), while the local church bells tolled all day. Later, local papers would be filled with the casualty lists and photos of the killed, wounded and missing.

The Battle of the Somme ended in a stalemate, with only a small amount of ground gained. Despite the horrific casualties on the first day, the top-brass ordered the attacks at the Somme to carry on for almost another five months. With the British and French suffering at least 610,000 casualties and the Germans enduring almost the same amount.

The Effects of the War

The British Army suffered its largest losses ever for a single day on that first day of the Battle of the Somme – 57,470 casualties, of whom over 20,000 were killed. During the course of almost five months of constant battle, British forces had taken a strip of territory just 6 miles deep by 20 miles long. In the end it had been the deteriorating weather conditions that had forced the Generals to call a halt to their major operations on the Somme.

For many of the men in the Pals battalions, the Somme was their baptism of fire. Some survivors, who’d witnessed the death and destruction of so many of their fellow soldiers, were left devastated. Up to then the politicians had managed to keep most of the truth about the fighting at the front from civilians back home.

After the first day of the Battle of the Somme, the reality of the war began to seep out. Included issues like the growing number of soldiers who were suffering from a battle-trauma named as ‘Shell Shock’, which we now know as combat-related PTSD. And that several of the fighting men with this condition were accused of being cowards and were ‘shot at dawn’ by firing squads of their fellow soldiers.

The authorities, however, now also began to worry that the shock and grief caused by massive battle losses could cause a form of home-trauma to set in. And some thought this gradually might slip into a form of distress-driven war-weariness. Which could then cause anti-war feeling to grow.

So, aware of the impact such losses could have, especially on small concentrated local communities who’d became saturated with grief. The authorities began to fear that the Pals Battalions, which had started in a spirit of patriotic camaraderie and communalism, might now become a factor for the growth of anti-war attitudes.

Conscription Takes Over

The 145 Pals battalions had allowed Kitchener to mobilise volunteers quickly for Britain at the start of the war. But after the Somme a more conventional form of enforced recruitment was quickly brought in. Conscription then took over as the main source of new recruits, with an age limit set at 18 to 41, which was increased to 51 towards the end of the war.

The local communal volunteering spirit of the Pals battalions was lost, but army units now received recruits from a much larger catchment area. This ensured that future losses were spread out more evenly across the home population. While this did not lesson the grief felt, it did reduce the chances of such feeling being concentrated, which helped deter the likelihood of outbursts of anti-war emotion.

The Accrington Pals

Mike Harding, an acclaimed popular comedian, folk-song writer and singer, was born in 1944, just a few weeks after his father was killed on a Lancaster Bomber that was shot down returning from a raid over Germany in the Second World War. Harding came from the Manchester area, not far from Accrington. After writing his song, The Accrington Pals, he wrote some notes about that first day of the Battle of the Somme:

“That day, 100,000 men took part in the battle; 21,000 were killed and 35,000 were wounded. Of the Accrington Pals, that battalion of 1,000 untried and unprepared men, 234 were killed and 350 wounded. Almost every family in Accrington had lost somebody. At first the Town Hall hid the truth, but as the news filtered through via letters from field hospitals and returned causalities, it gradually dawned that something terrible had happened. The people laid siege to the Town Hall, dragged the Mayor out and forced the truth out of him. It has often been said, and I can believe it, that the little town of Accrington never recovered from that ‘brilliant advance of July the First’. Among the 56,000 killed and wounded on that day there was not one general.”

To hear Mike Harding singing his song, The Accrington Pals, click on the link below: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MTpjOfEgPGk

_____________________________________

Article by Aly Renwick, who co-founded Veterans In Prison with Jimmy Johnson. Aly served for 8 years in the British Army from 1960-8.