In Britain today, on special occasions, the Household Cavalry will parade their noble well-bred horses before admiring crowds in London. Other Regiments in the British Army continue a tradition of adopting a certain animal as their military mascot. To act as a symbol for the unit and to take part in its ceremonies.

These are examples of what has become the evident and acceptable military use of animals. And all this fits in with the claim that: ‘We are a nation of animal lovers’. There is, however, another side to the MoD’s interaction with animals that the British people and tourists usually do not see, or hear about.

In April 2019, the ‘Daily Mirror’ newspaper published an article about the abuse of animals during military tests. These were a part of the MoD’s weapons research programme at the Defence Science & Technology Laboratory (DSTL) at Porton Down:

Almost 50,000 animals have been killed in military testing at a top-secret government research base, the Mirror can reveal. During a series of experiments, scientists blew up pigs, infected monkeys with biological weapons and poisoned guinea pigs with nerve gas. Figures seen by this newspaper show 48,400 animals were killed at the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory at Porton Down, Wiltshire, between 2010 and 2017.

Daily Mirror, 27th April 2019, article by Sean Rayment.

Dumb Animals?

In the history of Britain there have been continuous attempts to stop cruelty towards animals. The Metropolitan Police Act of 1839 sought to prohibit: ‘Fighting, or baiting, Lions, Bears, Badgers, Cocks, Dogs or other Animals’. Three decades later, in ‘The Descent of Man’, Charles Darwin stated that:

‘There is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties’. Darwin’s work on evolution helped to change the way humans viewed their relationship with animals and a more enlightened view started to emerge.

Some people, however, still call animals: ‘Dumb’, but it is human beings who create wars, including our modern ones. Animals, by their own volition, do not brandish rifles, or don suicide-vests – nor do they drive tanks, pilot warplanes or control drones. Their only involvement in conflict is after they have been co-opted and trained into specific roles by humans.

The creature most associated with combat is the horse, either for mounted fighting, or as a pack animal. Early use of ‘noble horses’ in warfare saw them pulling chariots, or carrying lightly armoured horsemen. Later, the knight and his powerful warhorse, both heavily armoured, dominated the wars in Europe for centuries.

Gradually, most armies developed cavalry units and the ‘mounted charge’ often became the centrepiece of a battle. The coming of mechanization and modern weapons as we entered the 20th century pointed to the ending of the cavalry charge in warfare. Britain, however, still used them in WW1, although that started to change after it had become evident that machine-guns would wipe out any mounted attack.

Horses & Shellshock

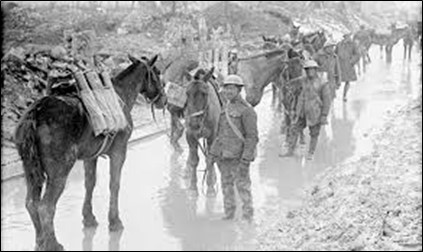

During one period of the ‘Great War’ as many as 1,000 horses per day were arriving at the front as replacements, to make up for the animals killed or wounded in the British Sector. The Army Veterinary Corps (AVC) treated over 725,000 horses during the war and over two-thirds were returned to duty. During the Battle of Verdun, in March 1916, German and French units lost 7,000 horses in one day due to the intense shelling from both sides.

After the major battles in WW1 the ground was saturated with the blood, flesh and bones of the causalities. Along with the human dead and wounded there were often a large number of horses among the victims too. While over 9 million soldiers died in the ‘Great War’, 8 million horses died also – some in cavalry units charging towards enemy defensive lines protected by machine-guns and barbed wire.

Other horses, living in the mud and exposed to shellfire and mayhem, perished from diseases, or from wounds, exhaustion and terror. While it is true that the horses were trained for their role, many were left traumatized and bewildered on the battlefield. Symptoms of ‘shell-shock’ – now known as combat-related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) – were detected among a number of the horses at the front and some were treated for this condition at the AVC’s animal treatment centres.

Animals at War

During WW1 there were pictures of wounded soldiers and sometimes ‘Shellshock’ was mentioned – to indicate how they were affected by the warfare. Often, these were censored, but images of maimed and distressed horses were totally missing. To let a ‘nation of animal lovers’ see what was happening to their ‘noble horses’ on the battlefield could have caused ‘war weariness’ and ‘opposition’ to grow.

Various animals were used for the conflict in WW1, with dogs, pigeons, canaries, camels, horses, mules, oxen and elephants being trained and then harnessed to carry out certain tasks. Some of the recruitment posters for WW1 attempted to manipulate the natural affection between man and horse to entice recruits. But the horses, unlike their riders, or handlers, had no say about taking part in the conflict – and they also had no concept of war and lacked any means of understanding it.

During WW1 the transport costs were considerably more for horses than for men, due to the space required and the cost of fodder. Britain’s need of horses was so great, however, that as well as requisitioning them from UK civilians, the military also imported them from other places – especially the US, Canada, Australia and Argentina. In its quest to keep up the supply of horses needed, the British Remount Department became a major international business, spending £67.5 million (a vast sum in those days) in its task to purchase ‘noble horses’ for the war.

Waler Horses

The Australian and New Zealand Mounted Divisions fought for Britain mainly in the Middle East during WW1, helping to drive the Ottoman forces into retreat from Egypt back to Turkey. The Australians mainly used hardy Waler horses, which were a cross between workhorses and thoroughbreds. Over 130,000 Australian horses, mostly Walers, were shipped out to take part in the war.

When the ‘Great War’ ended only one Waler horse was ever returned to Australia. The costs of transporting the rest of the horses – that had readily been found to carry the animals to war – was now found to be: ‘Too costly’ to take them home. So, the surviving horses were just sold off to locals to be worked to death, or butchered for meat.

Many of the Australian veterans were heartbroken about having to leave their Walers to this fate and some took their horses out into the scrub, or desert, and shot them dead. A similar situation occurred with the horses from Britain that had travelled to the front in France. Some officers were granted the right to have their mounts transported home, but most of the horses were sold off – mostly to French butchers.

The Fate of our Noble Horses

Humans have been fed lies and exploited as cannon fodder in wars since the history of organised combat started. Yet, as combatants, they mostly fight, either because they believe their ruler’s propaganda; or if not, because Homo sapiens at least have the capacity to adjust to their situation and come-to-terms with their predicament.

Conversely, animals, who have had their trusting nature exploited to take part in conflicts, can neither comprehend the human folly of war, nor rationalise their involvement in it. Conscripted and voiceless, they deserve to be regarded as fellow veterans and have better care taken of them, both during and after conflicts. In WW1, however, very little concern was shown to any of the veterans at the front – animal or human.

At the end of WW1, there were countless young men who had gone straight into the trenches and who knew no life save that of soldiers. Many were left traumatised and brutalised by their experiences. In London, a few years after the end of the ‘Great War’ on the anniversary of Armistice Day, 25,000 unemployed veterans marched past the Cenotaph in remembrance of the dead.

The veteran’s cry, written boldly on their banners, as they marched was: ‘NEVER AGAIN!’ To protest about their current plight, many pinned pawn tickets beside their medals. One of these veterans, George Coppard, recalled:

“Lloyd George and company had been full of big talk about making the country fit for heroes to live in, but it was just so much hot air. No practical steps were taken to rehabilitate the broad mass of de-mobbed men.”

As they marched, many of these alienated and disillusioned veterans remembered with a deep affection, not only their fallen comrades, but also those animals who had served alongside them throughout the war. Meanwhile, back in France, many of Britain’s ‘noble horses’ of the ‘Great War’ that had served through and survived the conflict, were now on display. Hanging on hooks in butcher’s shops as: ‘FRESH MEAT FOR SALE’.

Always, and especially next Armistice Day, please remember all the victims of wars and conflicts – combatants, civilians and animals. In the meantime, you can click below to listen to Leona Lewis singing ‘Run’, written by Snow Patrol:

Article by Aly Renwick, who co-founded Veterans In Prison with Jimmy Johnson. Aly served for 8 years in the British Army (1960-8).