A Veteran’s Legacy from Northern Ireland Tours-Of-Duty by Aly Renwick

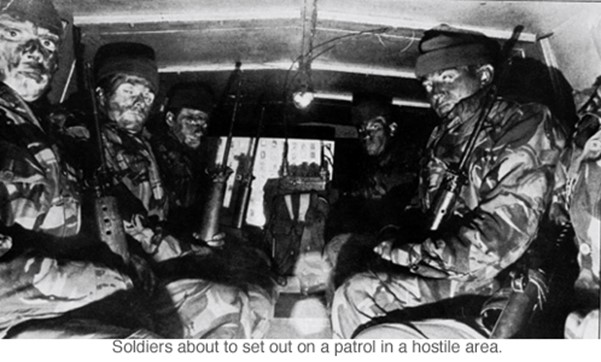

Operation Banner, the military name for the active deployment of British troops in Northern Ireland, lasted 38 years from 1969 to 2007. Over 3 decades ago, in 1989, violence from the Northern Ireland conflict disturbed the peace in an idyllic part of the English countryside. Gunfire rang out in Nayland, a tranquil Suffolk village, sending the local people scurrying for cover and requesting help.

This incident, however, did not involve the IRA, because the violence came from a returning British soldier: “When Corporal Michael King bought himself out of the British Army in 1988, he left the barracks in County Armagh with only one intention: to escape from what seemed to him an intolerable life. His two years of infantry service in Northern Ireland – street patrols, mortar attacks, deaths of fellow soldiers – had stretched his nerves to breaking point. He had resolved to abandon an eight-year military career, his friends in the regiment and to start anew on the mainland”.

Corporal King had settled happily into civilian life, living with his wife in the village of Nayland. All was going well until a day in April 1989 when, strolling home one Sunday afternoon, King suddenly believed he was back in the war zone on active service. Imagining IRA men in the surrounding area he ran home and took out his shotgun and what he had left of his army equipment. With his terrified wife hiding in a cupboard, he set up a firing position at the front window of the flat and started shooting. His first shots hit the vicarage, attracting the attention of other villagers who summoned help.

Soon Michael King was surrounded by police squads, including marksmen prepared to shoot. He had suffered a ‘Flashback’ – a symptom of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Without any knowledge then of this condition, he desperately tried to come to terms with what was happening and end his siege: “Worst of all he could find no explanation for his loss of control. Knowing nothing of PTSD or its treatment, he concluded himself to be ‘beyond help’, a danger to society, and called on the police marksmen to shoot him – ‘take me out’. But the police had sensed that the threat to the public had ceased, and that the only life in grave danger was King’s – at his own hand. Throughout the night two police officers talked to him and finally convinced him of the option of surrender.”

In April 1990 Michael King appeared before Ipswich Crown Court and pleaded guilty to charges of criminal damage. He entered a plea of mitigation that he had been suffering from PTSD, the first time this argument had been used in a British court. Sentencing King to a three year probation order, contingent upon him continuing a course of therapy, Justice John Turner said: “I am now satisfied you were suffering from a serious condition of trauma associated with your service with Her Majesty’s Army … and there is no real risk of a repeat, providing you undertake therapy”.

Around that time the people in British had also witnessed a series of accidental disasters over the recent past. Graphic press and TV coverage had created an indelible image of the tragedies: the sinking of the ‘Herald of Free Enterprise’ at Zeebrugge and the ‘Marchioness’ on the Thames; rail disasters at King’s Cross and Clapham; football tragedies at Bradford and Hillsborough; and Pan Am flight 103 exploding from the skies onto Lockerbie. With the public feeling sympathy, sorrow and sometimes anger, there was also a growing realisation that survivors – and often rescuers and witnesses – could afterwards suffer severe psychological problems.

Gradually, official recognition for civilians caught up in such incidents meant that short and long term counselling is now often provided and, in some cases, compensation has been paid for mental suffering. This recognition and treatment, however, is still lacking for veterans. Surely this is wrong, because while most civilians go through life without having to face such situations, troops, thrust into conflicts which continually throw up violent and bloody actions, will often experience traumatic events. In fact, it can be said that soldiers whole raison d’être is to train for and take part in them.

Michael King was just one of many soldiers who have suffered from PTSD and other rehabilitation problems after tours of duty in Northern Ireland. Because of the macho army culture most soldiers think it would be a sign of weakness to admit to showing symptoms. They need help from the Ministry of Defence (MoD) and the Government, but, as King’s experiences proved, this was not happening: “In 1984, just after the Harrods bombing, King had experienced an earlier, lesser episode of PTSD. It happened while he was on leave from his battalion’s intelligence section. He was arrested in an abandoned house which he deludedly believed to be the base of the bombers. ‘It came from all the same symptoms, lack of sleep, isolation, and a sense of guilt at why the English police, in the capital city of my country, should have to deal with a problem I should be dealing with as a member of the military. The civilian psychiatrist put it down to depression but told me to consult my battalion’s medical officer on return to base. When I told him the symptoms, he said, ‘Yeah, no problem, we’re being posted to Ireland, let’s just leave it there’.”

Instead of treatment, or a medical discharge, King received another tour-of-duty in Northern Ireland. Of the mental agony leading up to his second episode, King said: ‘If there had been a place, a person or even a telephone line I could have called when my life was ruled by PTSD symptoms, then all this would probably never have happened’.

While the actions of Michael King in Nayland frightened people, they did not harm anyone – so, the authorities could deal with his transgressions compassionately. In the years to come many other veterans of Northern Ireland, The Falklands, The Gulf War, Iraq and Afghanistan were to suffer the same sort of problems that Corporal King experienced. Because of this, and tragically usually for crimes of violence that did hurt others, lots of these veterans have ended up serving time in the HM Prison System.

Click on the YouTube Video link below, that shows some of the grim realities of tours-of-duty in Northern Ireland – set with the Status Quo song ‘In The Army Now’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_6f-Mkf9c6A

………………………………………………….

Article by Aly Renwick, who co-founded Veterans In Prison with Jimmy Johnson. Aly served for 8 years in the British Army (1960-8).